Part 1: The Economy on the Eve of Lockdown

Any event on the scale of the coronavirus pandemic, with its potential for death and dislocation, would Challenge any society, no matter the principles on which it was organised.

But this crisis plays out in a world that is fundamentally capitalist. What does experience of the pandemic teach us about how the world is organised and how it should be organised? How will established regimes across the world respond to the crisis, not just in dealing with immediate problems, but in pushing society

in the direction they would prefer?

This article is intended to be the first in a series that addresses these issues, in the form of answers to concrete questions to which activists will need to offer answers. But we begin with a story that shows just how capitalism’s inherent problems warp responses to the pandemic.

Envision is a U.S. company that supplies doctors and other staff to America’s privatised hospitals. Last year it was bought by KKR, a corporate investor using a typical manoeuvre of such private equity firms — essentially making Envision contribute to the cost of its own takeover by loading it up with debt: $7 billion

of debt.

Now Envision teeters on the edge of bankruptcy. The cause? Demand for non-coronavirus treatment has slumped, and with it Envision’s revenues and credit rating. The response? Cuts to the hours and pay of A&E staff on the front line of defence against the virus.

It is, of course, mad enough that the capitalist organisation of health care should threaten its provision in the very time when it is most needed. But there is a further, deeper, madness involved. The problems of Envision, and firms like it, could bring down the world financial system, threatening the productive economy just as it struggles with the pandemic and its aftermath. How this might happen is discussed further on in this article.

In Section I we discuss the state of the economy on the eve of the pandemic. (When we refer to ‘the economy’ we ultimately mean the whole world capitalist system. But this article aims to outline some technical issues for the non-specialist reader and so examples relating to particular countries are chosen for illustrative effectiveness, not to provide a systematic survey. Those who would like to explore further should consult the sources given in Appendix B.)

In Section 2 we claim that we face a dual crisis-one arm is the pandemic itself; the other is a fundamental problem of the capitalist organisation of production.

1. Was the Economy in a Strong Position Before the Lockdown?

The best measure of the health-in capitalist terms-of a capitalist economy is investment. If profits are not being invested then that is because capitalists are not confident of achieving an adequate rate of profit.

And, of course, if profits are not there to begin with, then investment will be hard to finance.

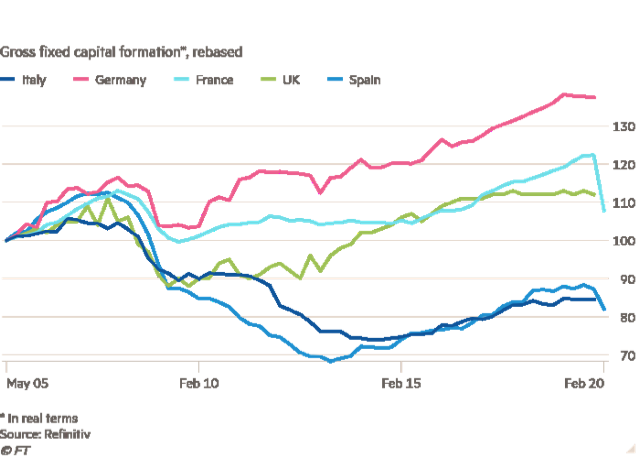

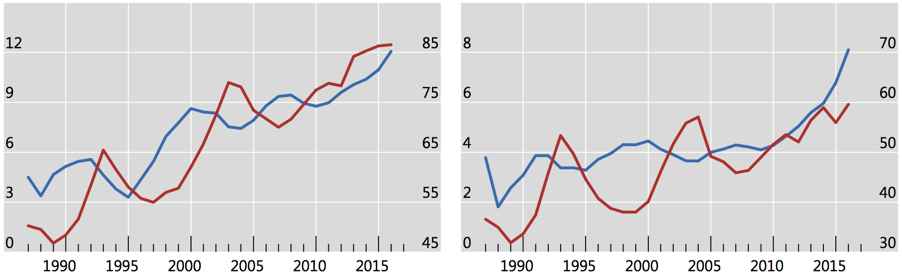

In Europe, investment tanked after the worldwide 2007-8 financial crisis, and except in Germany has either taken a lasting hit (in Spain and Italy it is little more than 80 per cent of what it was, in real terms, in 2005) or barely recovered to its level on the eve of the last crisis, as in Britain (Figure 1 ).

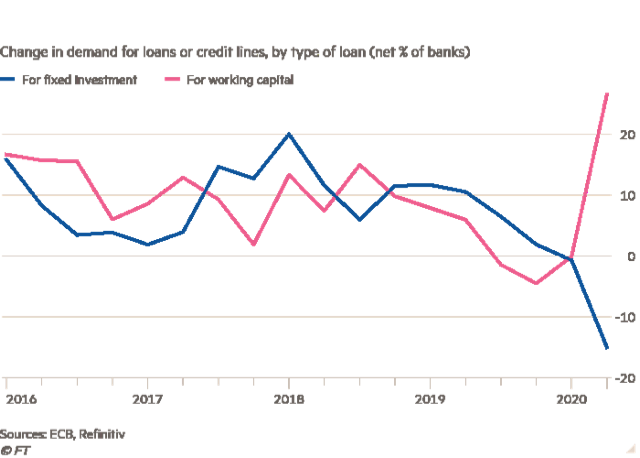

Moreover Eurozone demand for loans to finance investment had sharply slowed in the year before the onset of the pandemic. This was true of both borrowing for working capital (to maintain current production) and for fixed investment to renew and expand capacity. Since the onset of the pandemic demand for working capital, to keep firms ticking over under lockdown, has soared, but demand for investment capital has fallen off a cliff (Figure 2).

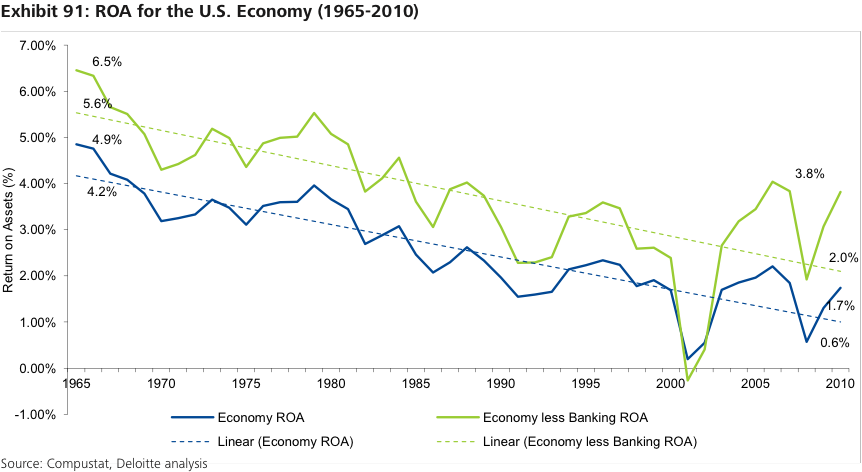

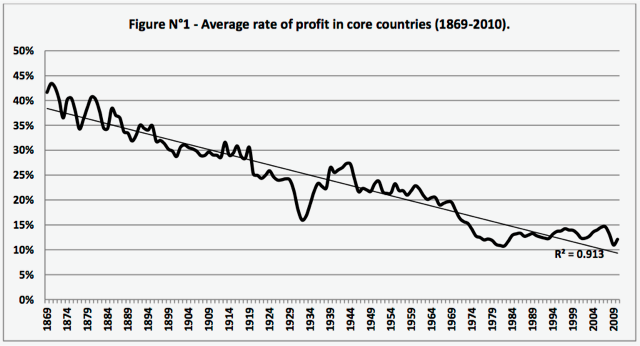

This is not just a matter of delayed or aborted recovery from the 2007-8 crisis. A wealth of research demonstrates that the inner story of capitalism since the Second World War is a relentless decline in profitability; this is true even in the United States, the largest and for many decades the most dynamic capitalist economy (Figure 3). The precise trajectory was modified by many geopolitical events, but by the first decade of the present century the rate of profit was at a historic low (Kliman (2011 ); Roberts (2016) adds information from many more economies).

The crisis was postponed by financial deregulation and government-inspired low interest rates, which together supported demand through by extending credit to anyone (especially consumers) willing to take it on, regardless of their real ability to repay.

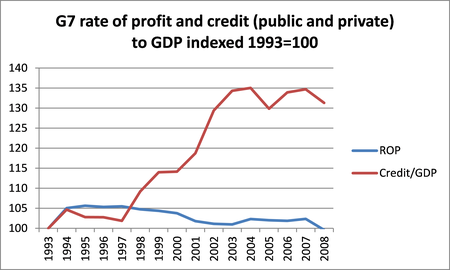

Total debt soared, even as the rate of profit sagged (Figure 4) in the major economies. The badness of these loans was disguised by financial engineering such as the CDOs and CLOs discussed above, but revealed by the 2007-8 crisis. (Note that although Figure 4 shows total borrowing, public and private, it is the private borrowing that creates the systemic risk.)

The result is, on one side, to enlarge the horde of ‘zombie enterprises’, just about profitable enough to service their debts, given that interest rates have been forced near to zero, but not enough to justify new investment; on the other, more profitable companies either sitting on mountains of cash, or returning capital to investors through buying back their own shares (which increases their apparent profitability but not the real profitability from production).

It is important to realise that the growth of zombie firms is not merely a result of cheap credit in the wake of the 2007-8 crash. Relative to the total number of firms, zombies have been steadily growing for 30 years, as Figure 5 shows (‘narrow’ definition: the proportion of firms earning too little to service their debts for three years in a row). What has shot up-doubled since the last financial crisis-is the proportion of firms whose stock market valuation is small compared to the value of their physical assets (the ‘broad’ definition).

The continued existence of these firms is immediately threatened if a new financial crisis breaks out, and especially if that then leads to disruption of production, slump and depression. An important detail is that the BIS study only includes firms whose shares are traded on stock exchanges. Private firms tend to be smaller and are more likely to be family businesses. Zombies are particularly prevalent among smaller firms – over a quarter of the these, against five to 10 per cent of the largest (Michael Roberts’ biog ‘The post-pandemic slump’ 13 April 2020).

If a post-pandemic crisis ruins swathes of smaller capitalists to the perceived benefit of larger ones, historical precedent suggests that this would lead to rise in support for the radical right. As the Financial Times reports, the risks to small businesses (not all of which will be strictly capitalist) are indeed high.

The so-called Business Bounce Back Loans scheme is aimed at small businesses with fewer than 10 employees and at the UK’s 900,000 sole traders and has lent £21.3bn in total to 745,000 enterprises; now bankers estimate that as many as half will default.

2. Is This a Special Crisis That Will End with the Lockdown?

There will be no ‘return to normal’ (and nor should there be), if ‘normal’ is defined to be the state of the world before 28 February 2020, the date of the first documented transmission of Covid-19 within the UK.

But it is important to realise that there are two crises involved. One is the pandemic and the measures taken to combat it. That is indeed special. The other crisis is in a sense entirely normal, and in fact more fundamental-a crisis in the profitability of the capitalist system. Each crisis will condition and constrain what would otherwise be the response to the other.

2.1 the Pandemic Crisis: Nature and Causes

To speak of the ‘nature’ of this crisis is peculiarly apt; the novel virus that is its immediate natural cause is as external to the essence of the capitalist system as a new asteroid collision would be to a future socialist society, as unrelated to the existing social order as bubonic plague in the Middle Ages was to feudalism.

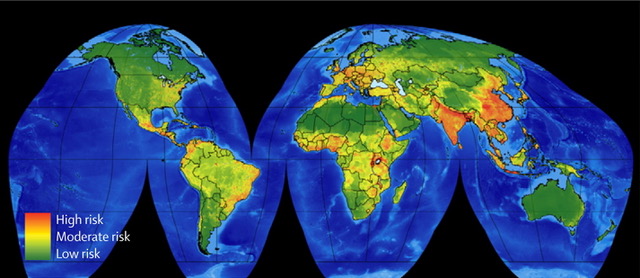

That said, although the virus itself is a fact of nature the material conditions of its origin are the capitalist organisation of mass agriculture and the consequences of this. Moreover, the response to the pandemic is necessarily conditioned by the capitalist environment that it exists in.

The origin of the present pandemic, like other recent pandemics such as SARS, lies in the interface between newly-capitalist, newly-industrial systems of food production and pre- and non-capitalist sectors. While this should rightly focus attention on the situation of marginal producers in the global South, it is important to avoid racist stereotypes about ‘wet markets’ and the commodification of exotic species as food sources.

These stereotypes risk being reinforced by maps such as that in Figure 6, which indeed shows a high risk of wildlife-to-human transmission of infectious disease across south and east Asia. But it also shows substantial risks in Britain and north-west and Central Europe.

As Rob Wallace, a mathematical epidemiologist, has pointed out:

As we industrialise the production of food, we also industrialise the pathogens that circulate among our livestock and crops. This mode of food production, producing, in livestock, cities of monoculture hog and chickens and other livestock and poultry around the world, is selecting for pathogens that are deadlier, more infectious, and of a wider diversity.

Now, that description accounts for pathogens that have made their way to the intensive farms within the spatial orbits of many a city. At the other end of regional production circuits, pathogens oft-spill directly from increasingly encroached-upon forests and the wild animals there, the reservoirs of exotic pathogens to which few humans have been exposed.

When we log, mine, or replace primary forest with plantation agriculture, we simplify the forest in such a way that deadly pathogens previously bottled up in wildlife are able to spring free. (Monthly Review May 2020)

Here too we see how the imperatives of the financial sector impact on the productive economy. After being bailed out in the 2007-8 crisis, Goldman Sachs moved to diversify its holdings, buying 60 percent of Shuanghui Investment and Development, a giant Chinese agribusiness that bought U.S.-based Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest producer of pork, a key food product in China. It also acquired ten poultry farms in Fujian and Hunan, within Wuhan’s wild foods catchment, and invested up to another $300 million alongside Deutsche Bank in hog raising in the same provinces.

2.2 The profitability crisis: nature and causes

Like many features of capitalism, the ‘nature’ of the profitability crisis is paradoxical. On the one hand it is essential, unavoidable, baked into the system by the logic of competition. On the other, as a feature of capitalism it is not a fact of nature but of the organisation of human society, which in principle humans can opt to change.

An inherent feature of capitalist competition is the tendency for profit rates to fall, resulting from each capitalist’s attempt to raise their individual profit rate by investing in more capital-intensive production processes. The overall capital, relative to total profit, goes up, and the profit rate goes down (a more detailed summary is given in Appendix A).

There are offsetting tendencies that limit this process, but they themselves are limited. In the final phase real investment falls off and attempts to profit through financial engineering proliferate. At that point any outside shock to the system can collapse the financial house of cards.

This is why the Envision case is so relevant. Even when capitalist profits are low, private equity firms such as KKR can capture wealth through the debt that finances takeovers. They can amplify this capture by bundling debts (in Envision’s case, around $2.5bn) into a piece of financial engineering called a collateralised loan obligation (CLO). That should sound familiar. CLOs are a close cousin to CDOs, the collateralised debt obligations that played a big role in the 2007-8 financial crisis.

That crisis was terrifying not just because of the amount of money involved-and the CLO market in the U.S. has doubled in size from $327bn in 2007 to $691 bn at the end of 2019-but because of the complexity and obscurity of the web of obligations created by this form of debt. Once one component begins to weaken, it pulls on a thread that could unravel this web in unforeseeable ways. Once no one can tell who is creditworthy, all credit dries up, and the real economy risks grinding to a halt.

Ultimately there is only one solution within capitalism-drastic reorganisation of the economy through business failure, job losses and poverty for millions. The immediate and longer-term prospects will be explored in a later article, but in the meantime see Appendix B.3.3 for preparatory reading.

2.2.1 Crisis or breakdown?

An obvious question, presented with the claim that the profit rate must tend to fall, is: does this mean that capitalism will eventually break down and expire of its own accord? Such a big question is, as might be expected, even more controversial than the original claim. This too large an issue to explore here, but Figure 7 offers food for thought.

A: The Rate of Profit and Capitalist Crisis

The idea that production can be organised without profit inspires holy terror in capitalism’s adepts. Their horror is evident in their term for the unprofitable but undead enterprises discussed in Section 1.

The idea that capitalism is inherently self-contradictory-that the search for profit logically implies the destruction of profitability-is thus enormously controversial.

Many books could be, and have been, filled with explaining, criticising, debunking, refining and reaffirming the argument that capitalism (unlike any previous social system) is crisis-prone entirely independently of any cause outside itself (see Kliman 2007 for a good account). Here we can do no more than outline it:

- capitalist competition for individual profit compels greater and greater investment in innovative machinery to replace labour

- but labour is the only source of profit, so the generalisation of new technology lowers the collective rate of profit, the rate for the system as a whole

- note: if the amount of capital grows faster than the amount of profit, the rate of profit falls by definition, even though profit as such has increased

- also note: there are many offsetting tendencies, but ultimately they are themselves limited; for example:

- more intense exploitation of labour (but there are natural limits to the length and intensity of the working day)

- reduction of wages (but workers cannot live on air).

- Thus the fall in profitability ultimately wins out.

- capitalism necessarily has a credit and financial system, unproductive in itself, but essential to capitalist production

- declining profitability

- leads to declining investment and general stagnation on the one hand

- on the other hand to increasing attempts to extract individual wealth through financial manipulation and speculation

- the financial house of cards can collapse at any time, triggered by many kinds of chance event but

- in times of boom the system can recover without fundamental change

- when the crisis spreads to the rest of the economy the underlying cause is the low rate of profit from production

- the only capitalist cure is to wipe out physical and financial capital, raising the rate of profit (and thus investment), not only if the amount of profit is not immediately increased but perhaps even if it is cut

- raising working class consumption at the expense of capitalist profit is not a cure; on the contrary it postpones the resolution of the crisis at the price of making it more acute when it breaks out again.

B: Resources

Know your enemy. Activists who want accurate information about important events (not only economic ones) really need to subscribe to the Financial Times. It is also an essential guide to what intelligent capitalists and their intellectual representatives are thinking. Unfortunately, much of its content is behind a paywall, although it has made a good deal of coronavirus-related content available free.

Michael Roberts’s blog An essential resource of up-to-date socialist economic commentary. Entries of particular interest are detailed below.

Socialist Economic Bulletin What it says on the tin; published by Ken Livingstone.

B.1 The Economy on the Eve of the Pandemic

Health and financialisation On the Envision buyout and its consequences (also multiple previous news reports)

Keynes or Marx? Does capitalism rely on consumption or investment?

B.2 Epidemiology, Agriculture, and the Pandemic

For a brief account, see this interview with Rob Wallace, which is based on the article detailed below. A full account of his argument is in the book referred to.

Longer article: ‘COVID-19 and Circuits of Capital‘, Rob Wallace, Alex Liebman, Luis Fernando Chaves and Rodrick Wallace, Monthly Review May 2020 (Volume 72, Number 1).

Book: Rob Wallace (2016) Big Farms Make Big Flu: Dispatches on Infectious Disease, Agribusiness, and the Nature of Science.

B.3 Profitability and the crisis

In theory and practice…

B.3.1 Marx’s theory, and why it matters

The claim that profit rates face inescapable downward pressure, resulting eventually in crisis, would be undermined if Marx’s assertion that the only source of profit is labour was shown to be untenable. The following work rebuts criticism of Marx’s theory.

Andrew Kliman (2007) Reclaiming Marx’s Capital: A Refutation ef the Myth ef Inconsistency, Lexington Books.

B.3.2 The 2007 crisis and its aftermath Michael Roberts (2009) The Great Recession.

Andrew Kliman (2011) The Failure ef Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes ef the Great Recession, Pluto Press.

Michael Roberts (2016) The Long Depression, Haymarket Books.

Guglielmo Carchedi and Michael Roberts (ed.s) (2018) World in Crisis: A Global Analysis ef Marx’s Law ef Profitability, Haymarket Books.

B.3.3 Post-pandemic prospects

Michael Roberts discusses the likelihood of a post-pandemic slump here and a permanent loss of output, even if growth returns to its previous (low) level here

This report discusses the OECD’s predictions for the UK.